Schema authoring guide

If you haven’t already, follow our Quickstart guide to get started with DMNO. Once you’re set up and ready to go, let’s dive in to writing a full schema for your project.

Project structure

Using DMNO, we define a configuration schema for your entire project that lives in a config.mts TypeScript file within a special .dmno directory at the root of your project. In a monorepo project with multiple child packages/services, we keep the root config, but we also break things up into multiple .dmno/config.mts files that live alongside each child and provide mechanisms for them to reference each other as needed.

A typical DMNO project structure:

Directory/ (root of your project)

Directory.dmno

Directory.typegen/ (generated types)

- …

- .env.local (your local overrides and sensitive values)

- config.mts (your config schema)

- tsconfig.json (dmno specific tsconfig)

Directorysrc/

- …

Directoryscripts/

- …

- package.json

- …etc

Directory/ (root of your project)

Directory.dmno/

- …

Directorypackages

Directoryapi

Directory.dmno/

- …

- …

Directoryfrontend

Directory.dmno/

- …

- …

Directoryshared-lib

- files… (no .dmno folder if no env vars are needed)

DMNO config files

Your .dmno/config.mts file will define settings for your project, including a full schema of all the config items used within your project. Your config file must include export default defineDmnoService({ //.... Here is an example:

import { DmnoBaseTypes, defineDmnoService, switchBy } from 'dmno';

export default defineDmnoService({ // project settings that affect DMNO itself settings: { redactSensitiveLogs: true, interceptSensitiveLeakRequests: true, }, // configuration schema that describes all the config / env vars used in your project schema: { APP_ENV: { extends: DmnoBaseTypes.enum(['development', 'staging', 'production']), value: 'development', // default value }, DISCORD_JOIN_LINK: { value: 'https://chat.dmno.dev', description: 'link for our users to join us on discord (uses a redirect)', }, CUSTOMER_SERVICE_EMAIL: { extends: DmnoBaseTypes.email, description: 'The email address for customer service', value: switchBy('APP_ENV', { // changes the value based on the value of APP_ENV }), }, },});Multiple .dmno/config.mts files in a monorepo

In a monorepo, aside from the root config file, each child service will have its own .dmno/config.mts file, and a few more options/features become relevant:

- specifying a service

namenow becomes more important - we can specify a

parentservice - we can now share config items across services (see sharing config for more info)

import { defineDmnoService, pick } from 'dmno';

export default defineDmnoService({ name: 'docs-site', // service name (optional - will default to `name` from `package.json`) parent: 'frontend', // parent service name (optional - if left unset, will default to project root service) settings: { /* add/override settings, otherwise inherited from root */ }, schema: { // we can use `pick()` to copy config items from other services APP_ENV: pick(), // defaults to picking from root service using the same key DISCORD_JOIN_LINK: pick(), CUSTOMER_SERVICE_EMAIL: pick(), USERS_DB_URL: pick('users-db', 'DATABASE_URL'), // copies from `users-db` service and renames the key

// more config specific to this service only DOCS_SPECIFIC_CONFIG: { value: 'foo' }, // ... },});Service names

Every service must have a unique service name within your workspace. You can set it in the service’s config, although if you do not specify a name, we will use the name field from that service’s package.json file.

We recommend you set it to something short - for example api instead of @my-cool-org/api - because you may be typing it into CLI commands (e.g., pnpm exec dmno resolve -s api) and it will be visible in several places in terminal output.

You’ll also use it when services need to point to each other in their configuration, like when using pick and parent as seen above.

Defining config items

Your service’s config has a schema which is a key-value object that describes all of the configuration your service uses. Each item has a definition that describes what kind of data it is, how to validate it, how to handle it within your build, a rich description that feeds into your IDE tooling, and in some cases, what the value is or how to generate / fetch it. More on that later.

We’ll start with a simple example from our own monorepo, and then dig into what all the options are:

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { // ... GITHUB_REPO_URL: { extends: DmnoBaseTypes.url({ allowedDomains: ['github.com'] }), description: 'Github link to the main DMNO monorepo', required: true, value: () => { return `${DMNO_CONFIG.GITHUB_ORG_URL}/${DMNO_CONFIG.GITHUB_REPO_NAME}`; }, }, },});Data types & extends

Each item is defined by extending some base type (whether explicitly or not) and adding additional overrides on top of it.

Most of the time, you’ll use existing data types, either from DmnoBaseTypes or from a published plugin - some by DMNO, some by others. These data types are factory functions, and accept settings that control reusable behavior like validation rules and docs info. You should almost always be able to accomplish what you need with existing types - but you can author your own reusable types as well.

These types are also used to generate TypeScript types for your config and give you type safety with docs when using your config in your application code.

The syntax for extends is rich, and best illustrated via some examples:

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { // common case where a datatype is called as a function w/ settings EXTENDS_TYPE_INITIALIZED: { extends: DmnoBaseTypes.number({ min: 0, max: 100 }), }, // you can skip the function call if no settings are needed EXTENDS_TYPE_UNINITIALIZED: { extends: DmnoBaseTypes.number, }, // string/named format works for a few of our basic types (with no settings) EXTENDS_STRING: { extends: 'number', }, // passing nothing will try to infer the type from a static value // or fallback to a string otherwise DEFAULTS_TO_NUMBER: { value: 42 }, // infers number DEFAULTS_TO_STRING: { value: 'cool' }, // infers string FALLBACK_TO_STRING_NO_INFO: { }, // assumes string FALLBACK_TO_STRING_UNABLE_TO_INFER: { // assumes string value: somePlugin.item(), },

// of course you can use your own custom types (or from plugins) USE_CUSTOM_TYPE: { extends: MyCustomPostgresConnectionUrlType, // additional settings can be added/overridden as normal required: true, },

// if no other settings are needed, you can use a shorthand and leave out the wrapping object SHORTHAND_TYPE: MyCustomPostgresConnectionUrlType, SHORTHAND_STRING: 'number', },});Sharing config between services

In a monorepo project with multiple services, DMNO allows config to be shared and composed across multiple services. In any service schema you can pick config items from other services to make them available within the service.

The pick function is a special kind of data type, and it copies all of the source item’s properties, not just the value. So you can think of the picked item as extending the data type of the original item. Use it like any other data type in an item’s extends property. There are 2 optional arguments to help specify the original item to pick from, with defaults being to pick from the root service, and use the same key/path.

import { defineDmnoService, pick } from 'dmno';

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { PICK1: { extends: pick() }, // picks from [root service] > `PICK1` PICK2: { extends: pick('other-service') }, // picks from `other-service` > `PICK2` PICK3: { extends: pick('other-service', 'OTHER_KEY') }, // picks from `other-service` > `OTHER_KEY` // ...Validations & required config

Validating your config BEFORE build/run/deploy is a huge part of what makes DMNO so powerful.

You can mark items as required: true and they will be considered invalid if the value is empty when we load your config. Additional validations will be skipped if this is the case. Note that if the config item has a static value set, for example value: 'some-val' then we will infer that the item is required. In the rare case that you plan on sometimes overriding the value to undefined, you can add required: false. Note that this required setting affects DMNO’s generated types as to whether the value might be undefined.

You can also attach custom validation functions, although most of your validation needs will likely be handled by reusable base types.

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { VALIDATION_EXAMPLE: { extends: DmnoBaseTypes.number({ min: 0, max: 100 }), required: true, validate: (val) => { if (!isPrimeNumber(val)) throw new ValidationError('Number must be prime'); }, }, },});Secrets & security

Items can be marked as sensitive: true and they will be treated accordingly. That means:

- They will NOT be exposed via

DMNO_PUBLIC_CONFIG, only viaDMNO_CONFIG - We will redact their values when logging them to the console via the

dmnoCLI - If the

redactSensitiveLogsservice setting is enabled, we will patch globalconsolemethods redact the value from all logs - If the

interceptSensitiveLeakRequestsservice setting is enabled, we will patch global http methods to intercept requests that send it to any domain not on theallowedDomainslist - Depending on the integration, we will help make sure you don’t accidentally leak them in bundled client-side javascript or server-rendered responses

To customize behavior, you can set sensitive to an object rather than true. Note that an empty object will still mark the item as being sensitive.

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { MY_SECRET: { sensitive: true, }, SOME_SECRET_TOKEN: { sensitive: { redactMode: 'show_last_2', allowedDomains: ['api.someservice.com'], }, }, ONE_PASS_TOKEN: { // data types may already be marked as sensitive and have customized settings extends: OnePasswordTypes.serviceAccountToken, }, },});Redact modes

For config values that have a common prefix, showing the first 2 characters will not be very helpful for identification. We provide several different redactMode settings to customize how the sensitive value is displayed when redacted. The following table shows the different modes supported:

| value | description | example |

|---|---|---|

show_first_2⭐ default | show the first 2 characters only | ab▒▒▒▒▒▒ |

show_last_2 | show the last 2 characters only | ▒▒▒▒▒▒yz |

show_first_last | show the first and last characters only | a▒▒▒▒▒▒z |

Docs & IntelliSense

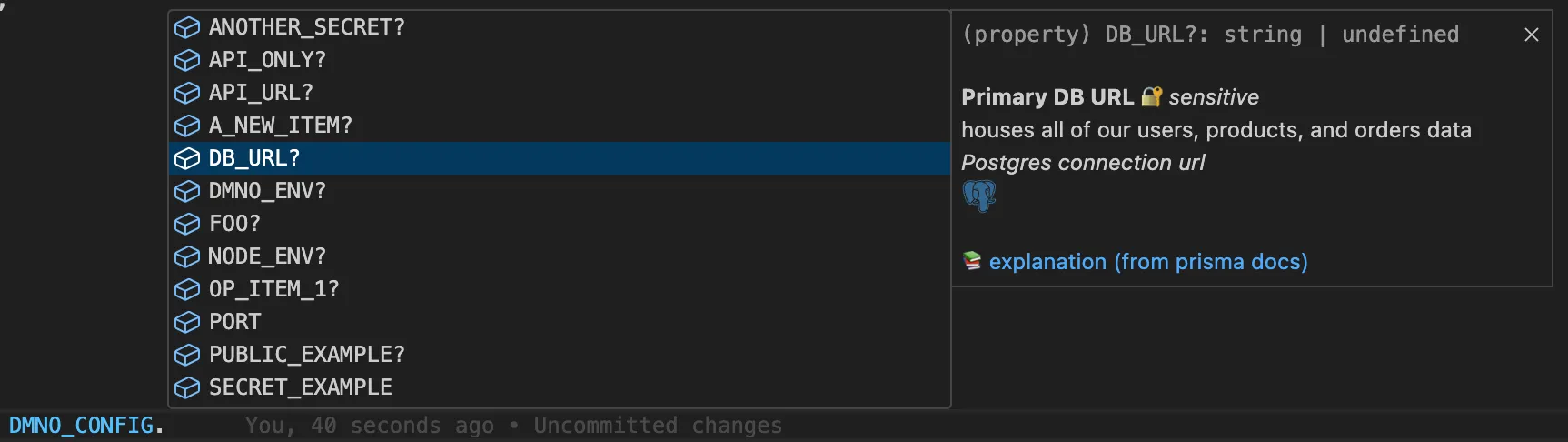

DMNO lets you attach additional information to items that serve as inline documentation about the item. This data is also used to generate TypeScript JSDoc comments for your config - giving you and your team ✨ magical IDE superpowers.

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { INTELLISENSE_DEMO: { required: true, sensitive: true, summary: 'Primary DB URL', description: 'houses all of our users, products, and orders data',

// description of the type of the data rather than this instance of it typeDescription: 'Postgres connection url', externalDocs: { description: 'explanation (from prisma docs)', url: 'https://www.prisma.io/dataguide/postgresql/short-guides/connection-uris#a-quick-overview', }, ui: { // uses iconify names, see https://icones.js.org for options icon: 'akar-icons:postgresql-fill', color: '336791', // postgres brand color :) }, }, },});An example of how the generated types show up with VSCode’s IntelliSense:

Dynamic vs static

Items can use dynamic: true or false to override their behaviour as to whether they should be bundled into your code at build time versus always loaded at boot time. This is only relevant for some integrations/projects, and it’s a big topic. See our dynamic config guide for more details.

Setting item values

While some tools may let you set only default values for config items, DMNO lets you set the value from within your schema for all situations.

This is possible because the dmno config loading process is broken up into 2 stages: first we load the schema, and then we resolve the values. While the resolution process does respect overrides passed in as process environment variables and other sources like .env files, many of your values may be set from the schema directly.

We can use static values, inline functions, or a resolver - which is basically just a fancy function that will be called during the resolution process and passed some contextual data about the config item and the rest of the resolved config.

An example of setting the value to each of these cases in our schema:

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { // static value (for constants or defaults planned to be overridden) STATIC_VAL: { value: 'static', },

// use an inline function which references other item values INLINE_FN_VAL: { value: () => `prefix_${DMNO_CONFIG.OTHER_ITEM}`, },

// using an instance of a "resolver" from a plugin RESOLVER_EXAMPLE: { value: somePlugin.fetchSecretItemById('xyz'), }, },});Internally, we even wrap the static values and inline functions into resolvers, so that we can always display some additional metadata about how the value will be resolved - even before attempting to perform the resolution. There is also a concept of branching to handle things like if-else and switch statements that point to more resolvers, leading to some very powerful composition capabilities.

A quick example to illustrate using our built-in switchBy resolver which switches between several branches based on the current value of another within your config.

export default defineDmnoService({ schema: { APP_ENV: { extends: DmnoBaseTypes.enum(['development', 'staging', 'production', 'test']), description: 'our custom environment flag', }, SOME_API_KEY: { sensitive: true, value: switchBy('APP_ENV', { // static values can be used if the value is not actually sensitive _default: 'dev123', test: 'test123', // sensitive keys we need to pull from somewhere secure using plugins staging: devSecretsVault.item(), production: prodSecretsVault.item(), }), }, },});You can author your own reusable resolvers - but you likely won’t need to for most use cases.